Oswald Spengler and Philosophy of History - Lucian Blaga

Translation from the Romanian "Ființa istorică", 1977

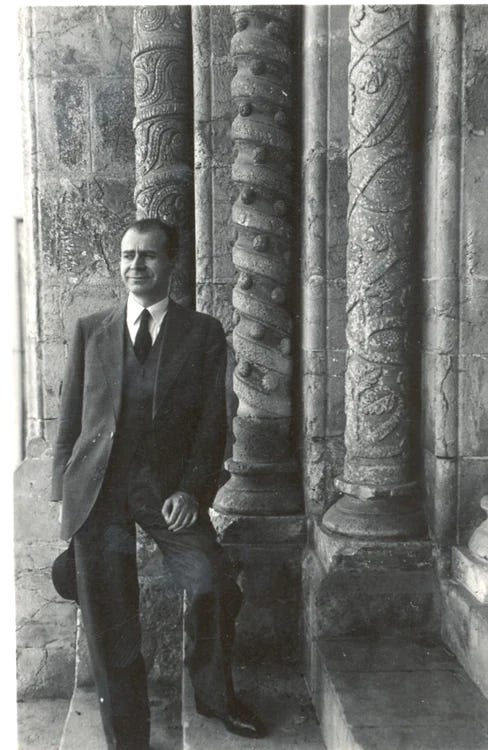

Small introduction to Lucian Blaga:

Lucian Blaga was born in Lancrăm, Sebeș county, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now part of Romania, on 9th of May, 1895.

Blaga was the 9th child of Orthodox priest Isidor Blaga, a graduate of the prestigious Brukenthal lyceum in Sibiu (German name: Hermannstadt), the main cultural and administrative center of the Transylvanian Saxons, also the longstanding capital of the Principality of Transylvania within the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

He completes his primary education at a German school in Sebeș (1902-1906), after which he completes his secondary education at the “Andrei Șaguna” high-school in Brasov (1906-1914), where his uncle Iosif Blaga was a teacher, a PhD in philosophy and the author of the first Romanian treatise on the theory of drama.

What follows is a Bachelor in Theology from the University of Sibiu (1917). Afterwards he studies philosophy and biology at the University of Vienna, where he obtains his PhD in philosophy with the thesis “Kultur und Erkenntins” (Culture and Knowledge).

Upon returning to Transylvania, now part of Romania, he contributes to major philosophical magazines such “Gândirea” and “Cuvântul” (the magazine where Mircea Eliade makes his debut) and publishes his first volume of poetry called “Poemele luminii” [Poems of Light]. He gets involved in Romanian diplomacy, occupying successive posts up to the rank “Plenipotentiary Minister” in Romania’s legations in Warsaw, Prague, Lisbon, Bern and Vienna.

His publishes his first philosophical work in 1924 entitled “The Philosophy of Style”, but we will return to this later.

Blaga would continue to write poetry for the rest of his life, managing 8 volumes, as well as writing 8 different plays and a novel. His poetry has been called “expressionistic” and “metaphysical”.

In 1936, he is elected a titular member of the Romanian Academy, for the occasion of which he writes a now legendary speech entitled “Elogiul satului romanesc” [The Eulogy of the Romanian Village]. In 1939, the University of Cluj creates a Chair of Cultural Philosophy especially for him.

In 1948, after the fall of the Monarchy and the instauration of a socialist dictatorship in Romania he is dismissed from his university professor chair for his refusal to express support for the new Communist regime and is forced to work as a librarian for the Cluj department of the Romanian Academy. He is forbidden to publish new books, and is only allowed to publish translations.

Blaga’s translation of Faust is to this day considered a pinnacle of the Romanian language, Blaga having to invent new Romanian-language procedures to faithfully render the text in Romanian.

In 1956 he is nominated to the Nobel Prize for Literature on the proposal of Bazil Munteanu of France and Rosa del Conte of Italy, the idea ultimately belonging to Mircea Eliade. The Romanian communist government sent two emissaries to Sweden in order to protest the nomination because Blaga’s philosophy, and especially poetry, was considered dangerous to the regime.

Blaga lived the rest of his life in a modest house in the village of Lugoj in Transylvania, barely making a living from publishing articles and his work as a librarian. He dies from cancer on 6th of May 1961, and is buried on 9th of May in his native village, gathering a crowd of thousands of Romanians.

Blaga, even from his youth, dreamed of creating a vast metaphysical system concerning all fields of philosophy. Thus, this philosophical creation consists of 4 Trilogies, each (usually) composed of two volumes dedicated to a philosophical field each, topped by a third volume developing their place in his metaphysics:

Trilogia cunoasterii (The Trilogy of Knowledge): About Philosophical Consciousness, The Dogmatic Eon, Luciferian Cognition, Transcendental Censure, Experiment and Mathematical Spirit.

Trilogia culturii (The Trilogy of Culture): Horizon and Style, The Mioritic Space, The Genesis of Metaphor and the Sense of Culture.

Trilogia valorilor (The Trilogy of Values): Science and Creation, Magical thinking and Religion, Art and Value.

Trilogia cosmica (The Trilogy of Cosmos): Divine Differentials, Anthropological Aspects, Historical Being.

Unfortunately, Blaga never wrote a Trilogy of Morals, which would’ve created a “total philosophical system”. Why he didn’t still mystifies scholars…

The essay that follows is from Historical Being, the last book he wrote, dealing with the metaphysics of history. Altough Blaga will explain his critique of Spenglers philosophy of history without recourse to his previous books, the writer presupposes some kind of familiarity with his philosophy of culture, particularly to the concept of “Stylistic Matrix”. If this translation does well, I will consider translating its essential parts.

Mircea Eliade said about Lucian Blaga that “Now we can rest assured that a Romanian philosophy can exist”.

That being said, I hope you enjoy this essay from one of the greatest man of letters of Romania, and as a small treat, I included a translation of Blaga’s most famous poem “Eu nu strivesc corola de minuni a lumii” [I do not crush this world's corona of wonders] in my friends (@TheEmperorIsNa1 on twitter) translation.

Oswald Spengler and Philosophy of History

The philosophy of history that Oswald Spengler has expounded in his book, The Decline of the West, has created a large echo all over the continent in the past couple decades. There are two reasons especially for which I’ve decided to discuss this philosophy which acquired its fame not only through its substance, but also through the alluring form of its presentation. On the one hand, Spenglarian philosophy illustrates — more plastically than any other philosophy — a certain cyclical conception of history, which of course cannot be ignored and which can be put in opposition to „progressive” conceptions of history. On the other hand, the philosophy in question represents a moment of outmost importance in contemporary thought. Taking an attitude towards it is, thus, by-itself necessary.

Spengler composed his conception of history – impressive without any doubt – under the influence of several thinkers. His conception has to be considered as not a beginning, but as a culmination of a certain mode of thinking, illustrated by several precursors. The philosophical mode of Spengler – through its organistic and morphological perspective towards history – sits under the influence of Goethe. This means that several other tutelary thinkers influenced the formation of Oswald Spengler, their influence being sometimes confessed, sometimes not. Therefore, in important and fundamental points of his historical conception, Spengler unconfessedly applies the monadological thinking of Leibniz. This will be discussed later. His method of reducing the creator-powers of culture to a quintessential human or divine type was appropriated by Spengler – like many vitalo-voluntarism criterias – from the philosophy of Nietzsche. Let’s remember how Nietzsche, in his genius young work about the origins of tragedy, circumscribed the two fountains of Greek culture through the mythical concepts of the “Apollonian” and “Dionysian”. We will have an opportunity to return to this point later. As far as the ideas of the “soul” of a “culture” are concerned, as being tied to a certain landscape, to a certain spatial vision, Spengler’s conception develops the cultural morphology of Leo Frobenius. Here are but some of the thinkers under the aegis of whom Spengler has composed his conception of history. The philosopher possesses, though, a power of synthesis and assimilation which is totally exceptional, so much so that no matter how ample his influences are, they cannot in any way diminish the eminence of his originality. In certain details of his philosophy, Spengler has also suffered serious influences from the Henri Bergson or from Houston Stewart Chamberlain. From the first one, Spengler took the distinction between matter as the object of science and life as the object of a living intuition. From the second one – a more alive understanding of Goethean morphology and so many details as it pertains to Western culture.

Spengler’s philosophy approaches the group of circular conceptions of time through the opinion that history is not linear, but circular, with possibilities of return. History then would be a series of finite phases, after the conclusion of which, the process can start from the beginning. History would have a beginning, a middle, and an end. It has a birth, it develops, it reaches maturity, ages and dies. Such a cyclical repetition of “universal years” was believed in Old Babylon. In Babylonian conception, cyclical development returns to “the history of humanity” as such, meaning to the known ecumenism of Antiquity. Spengler doesn’t admit a history of “humanity”. In his opinion, there exists only separate “histories” of diverse “cultures” which, in their development, cyclically go through similar phases.

A foundational idea for Spengler is this: any culture has to be seen as an “organism”; not metaphorically, but literally. Any culture is in its totality a real organism, animated by a “soul”. Under Spengler’s conception, a culture has its own specific soul, which is something else but the individual souls of the people which make up its collectivity. As it concerns the soul of a culture, Spengler develops, without always explicitly mentioning it, opinions which Leibniz formerly espoused as concerning the monads, ultimate unities of the substrate of existence. It is difficult to known if Spengler realised his ideas about culture are definitively very “monadological”. Cultures (and their souls) would be, by Spengler’s conception, impermeable in relation to others. This idea corresponds exactly to Leibniz’ conception about the impermeability of “monads”. Leibniz sustained that each monad is singular in its way and “without windows to the outside”. Exactly in this way, going by Spengler, the souls of diverse cultures would develop in-themselves and by-themselves, without windows to the outside. There would not exist, in Spengler’s opinion, any possibility for a man which belongs to one culture to penetrate into the being of another culture, to communicate with it up to a true understanding. This monadological situation and perspective, though, does not impede Spengler to pretend that he has a perfect understanding for all cultures.

The study of history for Spengler is diametrically opposed to the study of nature. In the study of nature, man proceeds analytically, systematically, mathematically, abstractly. Nature has a dead articulation. Nature has a “causality” and a reversible order. The study of history must proceed, conversely, physiognomically, organically, intuitively. History is eminently alive, nonmechanical, an authentic organism; history sits under the domination of an inner fatality and irreversible order. The object of exact and natural sciences is the world of causality, of matter, of laws: of number, of measure, of reversibility. The study of history has as its aim the life-development of a cultural organism. Historical phenomenon has no “laws” like a physical phenomenon. Historical phenomenon doesn’t have exterior causality, but an interior necessity, a “fate”. The appearance within a cultural frame of a great creation, be it poetic, be it religious, be it metaphysical, has its place in a certain moment of history; the appearance is fatal, being innerly determined by the organic development of the culture in question. A culture follows, in all its aspects, the example of a plant-seed which is from-the-beginning loaded with a bunch of limited possibilities. A culture realises its possibilities as a plant does. The forms of a culture appear all at their proper time, neither sooner, nor later; they are brought to light by the inner soul of a culture. Historical phenomena don’t produce each other as material phenomena do in the current schema of causality. Their temporal order is thus not a mathematical order susceptible to being inversed. Still, a certain order is constituted in the succession of historical phenomena, but here, there can only be talk of a life-order, “chronological”, unalterable. History is ruled by “fatality”, an irreversible order, that type of order which, before producing the fruit of a plant, doesn’t forget to spread leaves and to open its flowers. All these Spenglerian thoughts are fundament-ed on the idea that history is the development of an authentic organism in space and time, equipped with its own soul, which should not be confused with the individual souls of people.

In the greater part of his book, Spengler will trace the outline of the physiognomy of some of these cultural organisms and their souls. The soul of Ancient Greek culture is circumscribed by the term “Apollonian”. The significance of this vocable is known – full of restfulness and dreaming – from Nietzsche. We know that young Nietzsche tried to explain the substrate of Greek tragedy through the perspective of the Apollonian and Dionysian. Nietzsche proposed the Apollonian as the principle of individuation, of limited corporal existence. At the same time, the philosopher proposed the Dionysian as the principle of musical and orgiastic immersion into the metaphysical essence of the world, in the obscure-irrational of existence. Spengler picks up this operation, simplifying things a little bit. In order to characterise Greek culture, Spengler relies exclusively to the Apollonian element, taking the Dionysian element out of circulation. “The material body, solitary, limited, palpable and eternally present, lacking any perspective, in-itself sufficient”, is for Spengler, the symbol of the Apollonian soul which created Greek culture. Later, in the elaborations Spengler provides regarding Western culture, we see the Dionysian re-entering in its full right, with a significance obviously extended, easily reshuffled, and in any case under another name. Faustian is, following Spengler, the soul which creates Western culture. The Faustian is very closely related to the Dionysian, that ancient element which, in orgiastic and ecstatic rites of intoxication, would force individuals to limitlessness. The Faustian has as its special symbol the infinite; the Faustian consumes itself in imbibing the infinite. All forms of Greek culture and all forms of Western culture thus appear reduced to the Apollonian, in the first case, and the Faustian, in the second case. Apollonian is the statue of the naked man, Faustian is the art of the musical fugue. Apollonian panting draws well-contoured bodies (Polygnotos frescos), Faustian painting opens up infinite perspective out of light and shadow (Rembrandt). In this way, every culture is attributed a metaphysical substrate, a “soul”. It is the right moment to underline that again that Spengler does not understand this term (soul) metaphorically, but literally. These souls would be a kind of entities, a kind of monads, a kind of daemons which spring up and live in certain landscapes, and not in others, of the Earth. In my opinion, Spengler resumes ancient ideas with total seriousness, as would for example be the idea of “the genius of the place”. The particular soul of a culture is a certain kind of “genius of the place” . This genius, this daemon, takes the souls of the people who live in a certain landscape into its lordship, forcing them to serve it. People are the possessed of this daemon which is called the soul of a culture.

Spengler talks of many cultures which unfolded until now on this globe: Egyptian, Babylonian, Indian, Chinese, Ancient Greek, Arabian, Mayan, Western, Russian. When speaking of the Mayan culture of pre-Columbian America, Spengler has an accent of heartbreaking regret: Mayan culture wasn’t allowed to develop to its rightful end, being slaughtered in the flower of its youth by the Spanish-Christian invasion. Western culture is presented as being in decline, and the Russian one as just starting. Spengler doesn’t develop for us but only three of these cultures: Ancient, Western, and Arabian (The discovery of which in its full scope the philosopher is especially proud of). As it concerns other cultures, Spengler offers only vague outlines, and sometimes not even that. As it concerns the spatial symbol of Arabian culture, Spengler elaborates: that would be “cavern-space”.

The idea of spatial-symbols of different cultures, Spengler borrowed from Leo Frobenius, who tried to show that Hamitic culture has as its symbol the “cavern-space” and Ethiopian culture – “infinite-space”. Let’s list the spatial-symbols of several monumental cultures which Spengler stopped at either at length or in passing. Greek culture has as its symbol the isolated body (limited space). Western culture – three-dimensional infinite space. Arabian culture – cavern-space. Egyptian culture – the road to death. Chinese culture – the road in nature. Russian culture – the boundless plain (the steppe). The forms of a culture in its ensemble and diversity represents, according to Spengler, variations on one and the same motif, that of the specific spatial symbol. In the morphology of plants of Goethe, “sheet” is the fundamental form which the other forms of the plant variate on: root, stem, leaf, flower with petals, sepals, stamen, pustule. In the same way, in (Spengler’s) morphology of culture, all forms, including the styles of a culture, are seen as the modifications of a singular “spatial” vision.

Now, let’s proceed to the critique of this philosophy. If we gaze at things broadly, at “cultures”, we are inclined to admit that in the matrix of a culture one could spot, among other factors, a specific vision of space. When I composed my theory about culture and history, I accepted on this point both a Froebelian and Spenglerian suggestion. Stepping on this road with the reservations that are proper to it, I have sought to determine the visions about space of several cultures more closely and to correct some ideas proposed by Spengler. Thus, in the stylistic matrix of my own (Romanian) culture I discovered the “undulated space”. For Babylonian culture, I brought attention to the “storied space”; for Chinese culture – “space formed of wreaths/curls”; for Arabian culture - “veiled space”.

By developing our theory as concerns the stylistic matrix of a culture, I insisted broadly, returning and always amplifying the issue that the “style” and “styles” (when it is the case) of a culture cannot be considered as variations on the exclusive theme of a spatial vision. To such a unilateral, erroneous reduction that both Frobenius and Spengler decided on, after which they also tied, also in erroneous fashion, the spatial vision of a landscape itself into the “soul” of a culture out of which — no one knows how — it takes being from. I have formed an ontological and categorical theory about cultures and their styles. Man, anywhere he be from, in his being itself, has an existence in a double horizon. In the horizon of the world given by senses, man lives through auto-conservation; in the horizon of mystery, man aspires to reveals this mystery to himself through figments of culture (myths, religious visions, metaphysical conceptions, scientific theories, embodiments of art, moral ideas, etc.). For existence in the given horizon, man is equipped with a group of categories of consciousness with the help of which he organises his surrounding cosmos. For existence in the horizon of mystery, man is also equipped with a group of categories – of the unconscious – which are imprinted on all spiritual figments through which he, man, attempts to reveal to himself the mysteries of existence. The categories of the unconscious, abyssal categories; they sit at the basis of a style; they form a bundle of modelatory categories which complete one another in order to give all together a cosmo-genetic stylistic matrix. The “spatial” vision specific to a culture or a style is but only one of the multitude of categories which together constitute a stylistic matrix. That a stylistic matrix is composed of several categories, that it is not simple, but discontinuous, can be shown through the fact that they manifest as variables independent of each other. To try to, as Spengler did, to reduce a culture, a style, to a single base category (spatial vision) appears to me an operation just as narrow and wrong as it would be to reduce the categories of consciousness through which intelligence organises the world given to your senses to a single category. Imagine Kant reducing his ample table of categories of the intellect to a form of “spatial” intuition. But Kant has shown with sufficient arguments that for intellectual organisation of the world given through the senses, one needs an entire gamut of heterogenous categories. You can doubt the fairness of the selection of categories which Kant has made, but philosophers to this day hold strongly to the idea of their multiplicity. The figments of culture through which man reveals to himself the mysteries of existence have their own complexity; they have the appearance of “cosmoids”. If a figment of culture is equivalent to a world, then an indeterminate multiplicity of stylistic categories has to be, naturally, at its base too. A stylistic matrix represents therefore an entire gamut of stylistic categories. My theory concerning a stylistic matrix justifies the complexity of a culture and the immense variety of historical forms of a culture more philosophically. In order to simplify my vision about history somewhat, I felt the need to replace the image of the “matrix” with that of a “stylistic field”; this being done without essentially modifying the theory itself. Man as historical subject is a “stylistic field”. Any stylistic field represents the sum of certain determinant forces which work convergently; or, said another way, a stylistic field is made up of forces which imprint on spiritual figments or products of man. Anything which comes into being in a stylistic field carries its stamp, meaning any creative manifestation of man, be it in the domain of myth, be it related to technics, be it related to religion or economical production, be it related to metaphysics or state-organisation, be it related to art or to the world of facts as such.

I imagine stylistic fields as the eyelets of a net which covers the whole terrestrial globe. There is no void in the sphere of the stylistic fields. I also specify that the eyelets of these stylistic fields are not precisely isolated. They are in interference. Interferences of styles are even more frequent on Earth and in history than pure styles. Otherwise, to what extent pure styles exist anywhere is an open question.

With this more complex theory, but also more supple in-itself, of stylistic fields, understood as substrata of the spiritual and historical life of humankind, I offer, hopefully, a tool of research to historians which I consider more adjustable to research subjects than Spenglerian theory is, a theory somewhat simplistic, of a soul of a culture conceptualised mythologically as a “daemon” tied to a certain landscape.

Spengler’s theory is too rigid in its way, and especially very intolerant in the face of the infinite variety of cultures and historical forms.

One of the greatest difficulties which the application of Spenglerian theory about history meets comes from the idea of the impermeability of a culture in relation to another. Spengler, given that he conceptualised the soul of a culture and its history as an authentic monadic organism, finds itself in a kind of logical impossibility of renouncing the idea of impermeability. The theory of stylistic fields admits several procedures of adaption in object-knowing, being able to justify stylistic interferences, a phenomenon of universal frequency. In the perspective of the theory of stylistic fields , however, many other difficulties which the morphological perspective creates for itself by simplifying things excessively for the sake of an ideational monumentality disappear. The great part of Spenglerian ideas lead in fact to a very false historical interpretation. What, for example, does the affirmation of Spengler mean that a culture lasts for about 1000-1200 years as an organism passing through inevitable “fatal” phases which could be prophesised, but not foreshadowed?

How convoluted the consequences of this affirmation appear to me, especially when it concerns Western culture! This culture would presently find itself in its agonic phase: its future would only contain the perspective of a period of caesarean brilliance and supreme technical and material civilisation, then death. Spengler’s philosophy of history is of most part composed of ideas which do not derive from experience, but are “constructed”, constructed on the scaffold of a thought which remains ultimately mythological, Because mythologic is, without doubt, the thought that culture is an authentic organic body of a daemon which subjugates the human population which lives in the same landscape as the daemon.

The only suggestion which is truly fertile and susceptible to development from Spengler’s philosophy for me is that which concerns the specific spatial vision of a certain culture. Unfortunately, this idea appears in Spengler in a theoretical gearset which is totally unacceptable.

I do not crush this world's corona of wonders, 1919

I do not crush this world's corona of wonders, nor do I kill by reason, the mysteries I meet on my way in flowers, in eyes, on lips or graves. The light of others strangles the spell of the impenetrable, hidden in the depth of darkness, but I, I grow the world's wonder with my light - just like the moon with its white rays does not diminish, but trembling increases even more the mystery of the night, same way I enrich the shadowy horizons with grand shivers of holy mystery and all that is unknown changes to even greater unknowns under my eyes - for I do love flowers and eyes and lips and graves.

Would love to know the Romanian word for monadological

Well done.